Bertrand Russell and the Missile Crisis

How Bertrand Russell foretold the end of the world

Bertrand Russell was not at his most optimistic during the last week of October 1962, believing that we were all about to die, not at some distant point in the future, but soon–certainly by Christmas. Happily for humanity, Russell did not shy away from the role of bearer of bad news, quickly publishing a leaflet, informing people of their imminent demise.

YOU ARE TO DIE not in the course of nature, but within a few weeks. And not you alone, but your family, your friends, and all the inhabitants of Britain, together with many hundreds of millions of innocent people elsewhere.

WHY?

Because rich Americans dislike the Government that Cubans prefer, and have used part of their wealth to spread lies about it.

WHAT CAN YOU DO?

You can go out into the street and into the marketplace, proclaiming: “Do not yield to ferocious and insane murderers. Do not imagine that it is your duty to die when your Prime Minister and the President of the United States tell you to do so. Remember rather your duty to your family, your friends, your country, the world you live in, and that future world which, if you so choose, may be glorious, happy, and free.

AND REMEMBER:

CONFORMITY MEANS DEATH. ONLY PROTEST GIVES A HOPE OF LIFE.

[Russell, Unarmed Victory, p. 40]

Breathless stuff, to be sure, but, in fairness, the possibility of imminent death was on the minds of a lot of people during the last week of October 1962. President Kennedy's televised address on October 22nd, announcing the discovery of Soviet missiles in Cuba, and declaring a naval blockade around the island to prevent further Soviet shipments, had seemingly brought the world to the brink of nuclear war.

This was not a situation that Lord Russell was prepared to let pass without firing off a telegram or two. The first to Kennedy:

Your action desperate. Threat to human survival. No conceivable justification. Civilised man condemns it. We will not have mass murder. Ultimatums mean war. I do not speak for power but plead for civilised man. End this madness.

[Russell, Unarmed Victory, p. 39]

The second, to Soviet leader, Khrushchev, had a very different tone:

I appeal to you not to be provoked by the unjustifiable action of the United States in Cuba. The world will support caution. Urge condemnation to be sought through United Nations. Precipitous action could mean annihilation for mankind.

[Russell, Unarmed Victory, p. 39]

Russell also sent missives to Harold Macmillan and Hugh Gaitskell, but ironically enough not to Fidel Castro, despite Castro's bellicose rhetoric about nuclear reprisals and the destruction of Yankee imperialism.

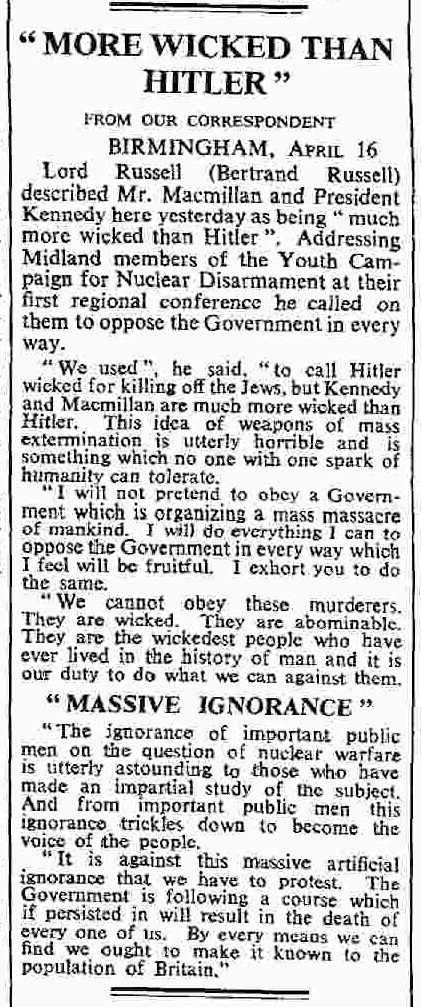

One has to admire Russell’s chutzpah. Only a year earlier he had labelled Kennedy and Macmillan “worse than Hitler”, and denounced them as the “wickedest people who ever lived in the history of man”, so it is surprising he’d suppose he might have any influence over them.

He did not, of course. However, in a surreal turn of events, he did get a response from Khrushchev, which became headline news around the world.

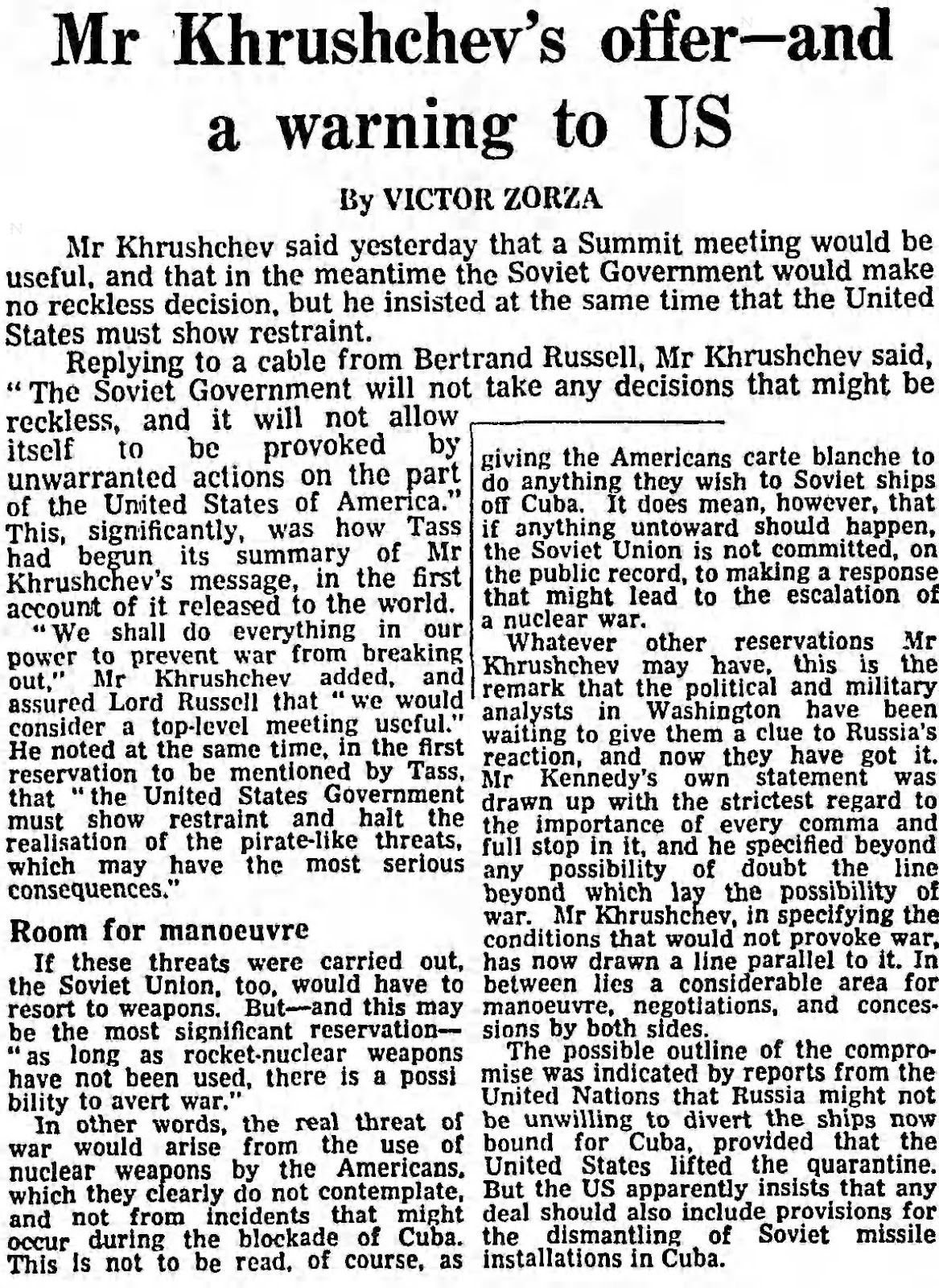

Khrushchev’s reply to Russell, released by Tass, the Soviet news agency, and obviously intended for American eyes, struck a conciliatory note. He assured Russell that "the Soviet Government will not take any decisions that might be reckless, and it will not allow itself to be provoked by unwarranted actions on the part of the United States of America." Most significantly, Khrushchev promised that "as long as rocket-nuclear weapons have not been used, there is a possibility to avert war," signalling room for negotiation and compromise.

The Kennedy administration took Khrushchev’s softly, softly approach as a sign that the Soviets were looking for a way out. The crisis reached its resolution following a private exchange of letters between the two leaders. The deal was that the Soviets would withdraw missiles from Cuba in exchange for Kennedy's public pledge not to invade the island. In addition, there was a backchannel agreement that American missiles would later be removed from Turkey. The world stepped back from the brink, and the missiles were dismantled and shipped back to the Soviet Union by December–just in time for the Christmas that Russell had feared nobody would live to see.

Russell struggled valiantly against the impulse to take credit for the resolution of the missile crisis, but he couldn’t quite hold himself back. The reality is that while Khrushchev used Russell’s telegram as a pretext to communicate to the Americans that the Soviets wished to de-escalate, he would have found another way to send the message if Russell had not sent his telegram. The idea that cold war geopolitical machinations turned on the intervention of a vainglorious philosopher is absurd. But not so absurd as to prevent Russell from suggesting to Ralph Miliband that that was exactly what had happened, when he claimed to have had “some voice in preventing war at the time of the Cuba crisis.”

Luckily for us, Russell’s fellow-travellers in the peace movement agreed with his assessment of his own importance in preventing World War III, and arranged a public celebration in his honour. Thanks to the gods of comedy, and the Guardian newspaper, we can get a sense of how this event passed off.

Look hard at a public thanksgiving and you will find irony in it. This afternoon began on the boundary of an explosives factory and ended with the circulation of a fire bucket. In between came gratitude for deliverance from the biggest catastrophe of all. And when it was all over an old, old white-haired man retired to his hilltop home a mile or so away from here to savour the freshest of a long string of public accolades: the greatest philosopher of his age, martyr, crank, and now—saviour of the world, no less.

This was how they saw Bertrand Russell in Penrhyndeudraeth today. Possibly a few of the villagers refused to be swept away on the wave of high post-Cuba emotion that was about the streets (they would be the ones peering narrowly from behind cottage curtains) as nuclear disarmers rolled in from Bangor, Aberystwyth, and other pacific strongholds. If so, they were alone with their doubts. For everyone else, a third world war was averted on the night of October 22, 1962, by a sheaf of telegrams dispatched (by way of Manchester, the historians had better remember) from the ennobled heights of Plas Penrhyn.

This get-together, we were reminded by a bilingual leaflet, was Everyman's way of saying thank you to Lord Russell. And here were extracts from the redeeming documents. Were these indeed the words that stayed the launching of a thousand missiles? "Apeliaf atoch i beidio a chael eich cythruddo," was one text sent to Mr Khrushchev. That, surely, would be enough to stop any belligerent in his tracks. (And Manchester's part in this transmission clearly cannot be overemphasised.)

[...]

Small boys had pinned to their backs notices which read, “I don’t want to die.” But generally it was an occasion for outgoing emotion, typified by the placard, “Thanks to Bert, We’re Not Hurt”–a sincere tribute, no doubt, though it seemed to sit rather awkwardly upon the author of “Inquiry into Meaning and Truth”.

[The Guardian, November 12, 1962, p. 16]

At this point, maybe you’re thinking that this is all a little unfair, and that Russell’s intervention in the missile crisis was admirable. So let’s reflect a bit on the things that Russell got wrong about Cuba.

First, he suggested variously that there were no missiles in Cuba, that if there were missiles they were not nuclear missiles, that if there were missiles, they were defensive only, and that if there were offensive missiles, they were only short-range missiles. All of this was just straight up wrong as was definitively confirmed in Khrushchev’s Memoirs.

Second, he was absurdly one-eyed in blaming the entire crisis on the Americans. He seemed entirely uninterested in the question of whether there were nuclear bases on Cuba, and if there were, how they got there and for what purpose. Ray Monk suggests that his unwillingness to engage with this issue was to avoid the charge of hypocrisy vis-a-vis his anti-nuclear credentials as a founder of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament.

Third, he was breathtakingly naive in supposing that Khrushchev was some kind of dove-like paragon in this whole affair. This is how he praised Khrushchev once the crisis was over:

I say to Premier Nikita Khrushchev that mankind owes him a profound debt for his courage and his determination to prevent war due to American militarism… I cannot praise sufficiently the sanity and magnanimity, the willingness to do all required to solve this overwhelmingly grave crisis.

[Russell, Unarmed Victory, p. 64]

However, the reality is that Khrushchev hoped to establish nuclear bases on Cuba before the Americans realised what had happened, on the grounds that the Americans would be unlikely to take military action against fully operational bases.

Fourth, his public pronouncements on the affair make your average Facebook post look sophisticated. The leaflet with which we started, for example, is risible—we’re all going to die because rich Americans are telling lies about the Cuban government, that’s what this is all about? Really?

Unsurprisingly, a good number of Russell’s contemporaries shared these reservations about his conduct during the missile crisis. Lord Gladwyn, for example, wrote as follows:

At the time of the Cuba crisis you circulated a leaflet entitled ‘No Nuclear War over Cuba’, which started off ‘You are to die’. We were to die, it appeared, unless public opinion could under your leadership be mobilised so as to alter American policy, thus allowing the Soviet Government to establish hardened nuclear missile bases in Cuba for use against the United States. Happily, no notice was taken of your manifesto: the Russians discontinued their suicidal policy; and President Kennedy by his resolution and farsightedness saved the world.

[Monk, The Ghost of Madness, p. 447]

The judgement of history has also been harsh. Ray Monk says of the “No Nuclear War over Cuba” leaflet that “its oversimplification of the issues involved would have been startling had they come from a schoolboy; from one of the greatest thinkers of our age, they were truly astonishing.” Similarly, historian Alan Ryan called it “hysterical and absurdly one-sided”.

But perhaps we should leave the last word to President Kennedy, who was courteous enough to reply to Russell’s discourteous telegram:

To Bertrand Russell,

I am in receipt of your telegram. We are currently discussing the matter in the United Nations. While your messages are critical of the United States, they make no mention of your concern for the introduction of secret Soviet missiles into Cuba. I think your attention might well be directed to the burglars rather than to those who have caught the burglars.

John F. Kennedy

[Russell, Unarmed Victory, p. 55]

Well quite.

Interesting post.

Russell 's change of heart between 1954 and 1962 may have been because,only one year after the death of Stalin (whom he several times called "wicked" one of his favorite adjectives ) it was too soon to tell if the new Soviet leadership would be more accommodating.

Eight years later,it is clear from your article,he was much more favorably disposed towards Krushchev.