Britains's Favourite Philosopher Guilty of Fare Evasion

The Curious Tale of C. E. M. Joad & the Train Ticket

If you had to name the most influential British philosophers of the 20th Century, the chances are that C. E. M. Joad would not appear on your list. In fact, unless you’re a philosophy enthusiast, it’s quite likely you’ve never heard of the fellow. This is not surprising. Joad enjoys no lasting intellectual legacy: his books are seldom read, he contributed no great original ideas, and he was regarded by his colleagues with, at best, polite indifference and, at worst, outright contempt. Bertrand Russell dismissed him as a plagiarist (and, apocryphally, refused to review his books on the grounds that “modesty forbids”), while academic philosophers found his habit of calling himself “Professor Joad” particularly irksome, given that no university had ever granted him such a title.

And yet, for a time, Joad was probably the most famous philosopher in Britain. During the 1940s, he became a household name thanks to the Brains Trust, a hugely popular BBC discussion programme where he, alongside Julian Huxley and Commander Campbell, would hold forth on all manner of topics with an air of great authority. His trademark phrase—“It depends what you mean by…”—became a national catchphrase, introducing the British public to the idea that before answering a question, one should first clarify its terms. It was, in its way, a valuable public service, even if it tended to give the (probably) misleading impression that philosophers do little more than quibble over definitions.

Joad also wrote a weekly column for a British national newspaper, the Sunday Dispatch, in which he opined on the issues of the day, such as the death of Tony the Performing Horse, what to think about in the dentist chair, beards, school uniforms, pornography and what he thought about as he crashed his car into a ditch. It was mainly fairly inoffensive fluff, but occasionally he dealt sensibly with an issue of importance. Here, for example, he argues in favour of euthanasia (Sunday Dispatch, March 22, 1942, p. 3):

I have never been able to see why a man should not be allowed to do what he likes with his own life. After all, we never asked for life. We were pitchforked into it without so much as “by your leave,” and we are, therefore, so far as I can see, under no obligation to make the best of a bargain that we never contracted.

[...]

Here, for example, is a man suffering from incurable cancer. Racked by perpetual pain, he longs to die. Yet, as the law stands, no doctor can confer upon him one of the greatest gifts of science–the boon of an easy death.

It must be said, though, he does rather go off the rails in his final paragraph:

Our community is fighting for its life. We don’t want to carry more passengers than we can help and take the time of able-bodied people to look after them.

Joad’s column ran from January 1942 until his death in April 1953. In fact, the Sunday Dispatch reported that he completed his final column only an hour or two before he died, at that point writing from his bed, which had been moved into his book-lined study. However, by this time, Joad’s reputation lay in tatters, wrecked by a scandal of his own making that made headlines around the world.

The source of the trouble can perhaps be traced to a passage that appeared in The Testament of Joad, a book he wrote in the mid-1930s. Here’s what it said (page 54):

When I am in my vagrant mood, society…appears to me as something to be preyed upon–I think of it as a great cow, whose udders are for the privy squeezing of the supple fingers of the vagrant… For example, as a vagrant I cheat the railway company whenever I can, returning on the next day with a cheap day return ticket or alleging, when I arrive ticketless at my destination, that I entered the train at a station nearer to it than was in fact the case.

It turned out that Joad wasn’t just spinning a line–on one occasion, at least, he really did set out to cheat the railway company.

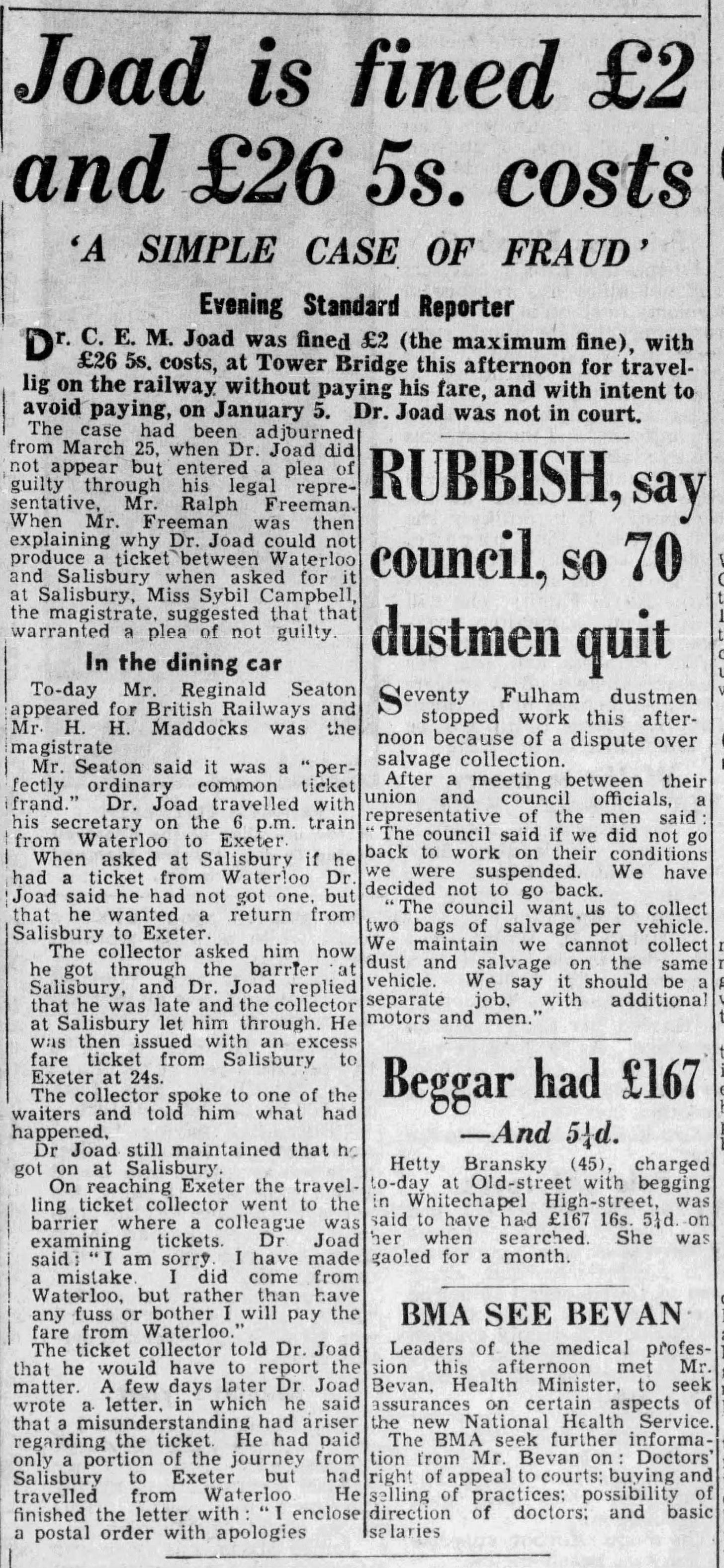

The story of his train shenanigans broke in the press on the evening of April 12, 1948. Here’s how the Daily Telegraph (page 5) reported on it the next morning.

Dr. Cyril Edwin Mitchinson Joad, of East Heath Road, Hampstead, was fined 40s and ordered to pay 25gns costs by Mr. H. H. Maddocks at Tower Bridge police court yesterday for travelling on the railway without having paid his fare between Waterloo and Salisbury, and with intent to avoid payment.

[...]

Mr. R. E. Seaton, prosecuting, said the offence was “a common ticket fraud.” Dr. Joad and his secretary joined the Exeter train at Waterloo on Jan. 5 and booked two places for dinner. After the train had passed Salisbury he was asked for his ticket. He said he boarded the train at Salisbury and he paid 24s for the fare from there to Exeter.

When challenged later by the collector, who pointed out that he had booked two dinners on boarding the train at Waterloo, Dr. Joad repeated that he had got on at Salisbury.

In all, he denied four times that he had travelled from Waterloo, but at Exeter admitted he had made a mistake and tendered the full fare from London. This was not accepted, and next day he forwarded the money.

Joad, via his solicitor, tried to pass off the incident as a giant misunderstanding, though it’s hard to credit that during the course of his journey he managed to forget where exactly he initially boarded his train.

Sixteen days later his solicitors wrote about the “extremely unfortunate incident” and referred to the repercussions which any prosecution “would have on a person of the standing of our client who is, of course, the internationally known lecturer and author.”

The solicitors explained that it was the custom for his secretary to obtain the tickets, but on this occasion Dr. Joad told her no ticket would be necessary for him to Salisbury as he had a return half to that point. After paying the excess to Exeter he discovered to his dismay that he could not find the return half which he had believed was in his possession. (Daily Telegraph, page 5)

Mr Maddocks, the presiding magistrate, clearly wasn’t buying that excuse, stating that there was no doubt about Dr. Joad’s guilt, and that the fine should be the maximum available for the offence, 40 shillings.

The fallout was brutal and quick. Within a week, the BBC had thrown him out on his ear, announcing that he would not be taking part in the final Brains Trust broadcast for which he had been contracted, and giving no indication that he would ever appear again. Joad seems to have known that this marked the end of his television career, commenting to the press that he didn’t know whether he’d broadcast again. It also marked the end of his hopes of attaining a peerage, which were well-founded until his fall from grace.

On April 25, 1948, less than two weeks after his conviction, Joad used his Sunday Dispatch (page 3) column to comment on his downfall. It makes for a poignant read:

You board a train at Waterloo for Exeter, thinking yourself to have the return half of a ticket to take you as far as Salisbury. You are sitting in the restaurant car having had dinner and, somewhere after Salisbury, the ticket-collector comes for your ticket. You ask to pay from Salisbury and do.

You then feel in your pocket for your ticket from Waterloo to Salisbury and find to your dismay that you haven’t got it. The ticket-collector comes again. “I am told,” he says in effect, “that you got in at Waterloo,” and because you are you and are famous and it is still the dining-car everybody is looking at you, you shrink from the publicity of a fuss and a public explanation and recantation and say: “Oh no, I did get in at Salisbury”–and then, out of pride and folly and because everybody is still listening to you, you go on saying it, lying in fact like a trooper, and also like a fool, since you have omitted to remember that you are famous and that, of course, the attendants noticed you when you took a dining-car ticket and tried to book a seat at Waterloo.

And then, when the thing comes to court and you propose to plead guilty, since you did, after all, make a false statement–make it, in fact, a number of times–instead of being treated like dozens of others and dismissed with a £2 fine and no mention in the papers, you find eminent, eloquent, and forcible counsel engaged to prosecute you, court full of newspapermen, and then in the evening and again the next day all the headlines blazing out at you, blazing out not once but twice, and then, when the B.B.C. dispenses with you, blazing out yet a third time, and you feel as if you were standing in the pillory with no clothes on and that everybody knows about you, recognises you, and is looking at you.

Obviously, that can’t have been much fun, but our sympathy should be at least somewhat tempered by the fact that his account of what happened that day just doesn’t stand up to scrutiny.

Why was he carrying around the return half of a train ticket in his pocket? Why didn’t he check if it was there before he boarded the train or at the very least before he encountered the ticket-collector? Why didn’t he explain to the ticket-collector that while he had boarded at Waterloo, he already had a ticket that covered his journey to Salisbury? Why didn’t he immediately alert the ticket-collector when he discovered he didn’t actually have a ticket for the first part of the journey?

Even if we think there is a plausible explanation for these omissions, we still have the difficulty that Joad was caught and prosecuted for doing the thing that he explicitly stated he liked to do in a book he wrote some ten years earlier. Therefore, the question is which is more likely: that he didn’t actually do the thing that he had previously stated he was in the habit of doing, and it was a mere coincidence predicated upon an unfortunate confluence of circumstances that led to him being prosecuted for it, and pleading guilty to the charge; or that he actually was in the habit of fare dodging, as he previously claimed, and in the end he got caught.

With cameras everywhere I of course now pay my fare on the subway and never shoplift anywhere, but when I was younger and there were no cameras, not paying your fare and shoplifting in supermarkets or big stores (never in small businesses) was considered to be cool and rebellious. I had a girl friend in the 1980's who shoplifted every time we went to the supermarket.

I used to shoplift in big bookstores when I was in the university until I got caught, but talked my way out of it offering to pay and apologizing. I can't see anything wrong with that. They're the small "rebellious" gestures of the little man or woman against the giants who own and run the system.