How the English Are the Best in the World

Everybody and everything in England is the best

Back in 2018, Liam Fox, Tory MP and Brexiter, penned a paean to British self-confidence. “Everywhere I go across the world,” he wrote, “everyone I meet tells me that they believe in Britain. They want to buy British products, use British services, learn English. They trust our laws and our financial services, they admire our Armed Forces and they envy our universities.”

But, alas, there’s a problem–we Brits just don’t understand how great we are: the world, Fox informed us, needs a confident Britain (he didn’t explain why), and Britain can and should be confident.

If only Dr Fox had had access to a time-machine. He would have felt right at home in the Britain of the roaring twenties–an era when national self-confidence wasn’t merely a political aspiration, but an article of faith manifest in the nooks and crannies of public and private life.

As documented with delicious irony in the 1931 book, The English: Are They Human?, written by G. J. Reiner, a Dutch visitor to our island paradise, the closing years of the 1920s witnessed a Britain that had mastered the art of self-congratulation.

This was Britain at its territorial zenith, when the empire covered a quarter of the world's land surface—and seemingly every British newspaper covered a quarter of its pages with assertions of national preeminence. The England of 1929 didn't merely believe it was on balance the best—it believed it was superior in absolutely everything, right down to its dustcarts and station posters (though the posters were pretty cool).

So, with the help of Professor Renier, our estimable guide to a forgotten and now foreign land, let’s take a look at the myriad ways that the English were in that benighted age simply the best.

Let’s start with our capital city, London–definitely the best in the world, especially in June, according to the Daily Express (12 June, 1929):

No town on the face of the earth is more brilliant than London in June, no city more satisfying or more faithful to its tradition. And yesterday London, under its flaming sun, was magnificently in June.

Also the healthiest city in the world, according to the Star (3 July, 1929), largely to be accounted for by the “uniformly good sanitation and water supply”.

Happily, England’s countryside by no means pales in comparison. On 10 June, 1929, the Daily Express waxed lyrical about the “ineffaceable” beauty of England, when the rain has “cleaned and sweetened” the whole countryside:

[T]here is not a landscape in the world we could exchange for England’s. Bring back to memory the choicest foreign scenes, and a carpet of bluebells under the soft green of an English copse will outmatch them all.

So we’ve dealt with town and country, next the people. Also, clearly top notch. Evidence to that effect could be found in American immigration policy, which had been amended to allow in twice as many of the British, celebrated in the Sunday Express with the headline “America Picks the Best” (July 7, 1929).

It goes without saying, obviously, that English women are preeminent–the best dancers in the world (Guardian, 27 June, 1929), more developed than other women (Daily Express, 10 June, 1929), and the “greatest wonder of the world” (Sunday Express, 19 June, 1929).

If the film director, R. E. Jeffrey, writing in the Evening Standard (29 June, 1929), is to be believed, then probably the British accent has something to do with the esteem in which we are held, since it “contains the quality which makes it better than any other voice in the world for reproduction”.

Okay, we’ve established that England has the best cities, countryside, people, women and voices, so what’s next? Zoos. According to the Nation (4 May, 1929), Britain has the best:

The Zoo… it is, I do not doubt, the best, the most humanely conducted, the most scientifically valuable, the most admirable in every respect of all Zoos.

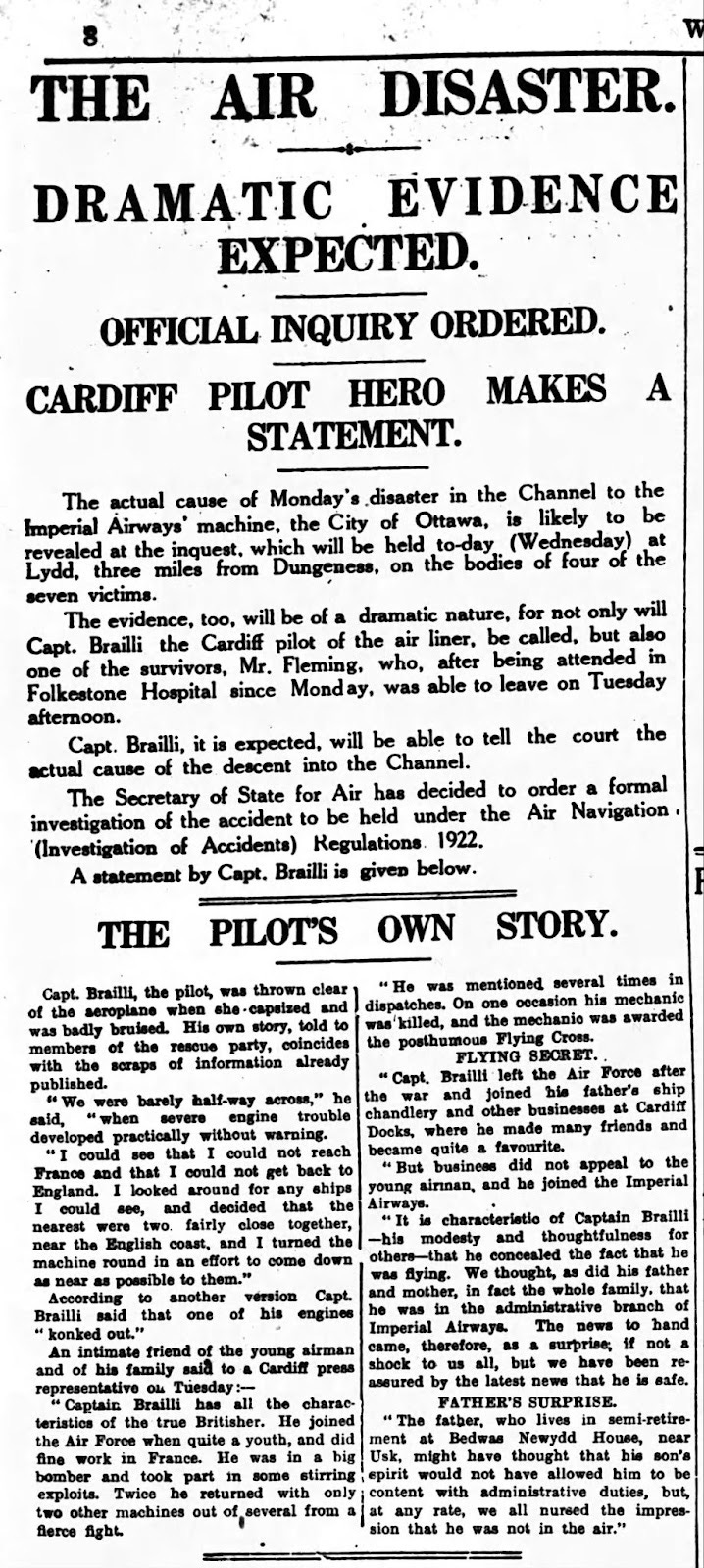

To zoos, we can add an airline–“The record of Imperial Airways for safety and regularity is the best in the world” (Star, 18 June, 1929)–the “gayest underground stations in Europe” (Guardian, 20 October, 1929) and, according to the Sunday Express (20 October, 1929), the “most famous piece of statuary in the world–the elaborate and imposing fountain which was surmounted by the statue of Eros, in Piccadilly Circus” (eat your heart out, Rome!).

At this point, it will come as no surprise to hear that the institutions of the British state are also unsurpassed. Take our judicial system, for example–obviously, “the finest in the world” (The Times, 27 March, 1929), with the “best judges and the most sensible juries in the world” (Daily News, 28 June, 1929). Similarly, our Civil Service–”for efficiency and incorruptibility it has no equal in the world” (Daily Herald, 24 March, 1930).

Consider the humble British Post Office (happily, in the days before unruly IT systems and wrongly incarcerated subpostmasters):

It has a dignity all its own, and includes in that tradition some of the best characteristics of the British race. The regularity, steadiness, and perseverance with which the many phases of its work are pursued have a striking resemblance to the Army and Navy which have carried British influence to remote corners of the earth. (Supervising, 1 February, 1930).

The natural question to ask of all this preeminence is from where does it originate? Possibly from the British hearth, since there is “nothing in the world to match the English home” (Evening Standard, 30 December, 1927), a happenstance that might also explain why “Englishmen make the best butlers, footmen and grooms in the world” (Evening Standard, 2 April, 1930).

Oddly, there is no claim for English superiority in matters culinary, a troubling oversight, it will be admitted, but happily it is accepted that “the best waiters in the world are the fully qualified English ones” (Evening Standard, 22 February, 1929) Also, the produce of English farms and gardens “is the best of its kind in the world” (Daily Mail, 26 October, 1929), which is a consolation.

At this point, it does rather feel it would be quicker to list the things that the English are not the best at–rather as when the hero of Three Men in a Boat informs his doctor that the only malady from which he does not suffer is housemaid’s knee.

But let’s end with a couple of the more audacious examples of English self-confidence.

The weather–with the best will in the world, it’s hard to think that the British weather is unsurpassed in all the world, on the grounds that it is…not. But that is to underestimate the confidence of an Englishman drunk on the glories of Empire and Morris dancing. Hence the Sunday Express on July 14, 1929:

Let us cure ourselves of the habit of pretending that the English climate is the worst in the world. In fact, it is the best in the world.

You might suspect that the Express has lost its mind, but eight months later, it doubled down, claiming that England is “the only country in the world where men and women can be out of doors on every day of the year”, an utterly bonkers assertion (why not Belgium or France, for example?), but one which does demonstrate admirable self-belief.

Finally, despite everybody and everything in England being the best, the English remain self-effacing and modest, as recognised by the Guardian, whose London correspondent wrote that we are “the most self-deprecating people on earth” (Guardian, 16 January, 1930). This puts Liam Fox in something of a bind—how do you restore confidence to a nation that historically has always been convinced of its own superiority while maintaining its preeminence in the realm of modesty? It seems, alas, that you can’t have your humble pie (no doubt, the best humble pie) and also eat it.

With thanks to G. J. Reiner.

My mother was an anglophile, basically because they stood up to the Nazis and so I grew up listening to Gilbert and Sullivan, "For he is an Englishman", etc. Orwell's essay, England, your England, is British chauvinism, but convincing to me.