On Sociobiology, Edward O. Wilson, and a Pitcher of Water

A blast from a science war of the past.

In today’s heated climate, where public figures, ideas, and long-standing academic theories are scrutinised through the lens of politically motivated social media activism (both left-and right-wing), it is easy to think of “cancel culture” as being distinctively modern. However, the phenomenon of pillorying ideas that don’t align with the current zeitgeist, and monstering their proponents, with cancellation the aim, isn’t new. Let’s take a trip back to the 1970s, and the publication of Edward O. Wilson’s magnum opus, Sociobiology, for an example from the world of science, the ripples of which were felt for at least a decade.

Wilson’s book was initially greeted with enthusiasm, with biologists, and biology-friendly social scientists, favouring it with good reviews. However, an activist organisation called Science for the People (which self-identified, of course, as anti-imperialist, and opposing racism, sexism and elitism), and the Sociobiology Study Group, a collective opposed to sociobiology, that included Wilson’s Harvard colleagues, Stephen Jay Gould and Richard C. Lewontin, moved quickly to do something about this regrettable situation.

In a famous letter published in the New York Review in November 1975, Gould, Lewontin, and others, claimed that human sociobiology – the idea that both environment and biology determine human behaviour – was scientifically unsupported, morally repellent, and politically dangerous. The letter drew a link between sociobiology and Nazi eugenics, and suggested the theory was motivated by a desire to maintain the societal status quo, ensuring the maintenance of privilege for those groups in society that already possessed it. Thus:

Wilson joins the long parade of biological determinists whose work has served to buttress the institutions of their society by exonerating them from responsibility for social problems.

The letter concluded with the instruction to take sociobiology seriously, not because it is good science, but, in effect, because it’s dangerous.

Wilson was clearly shaken by the publication of the letter, writing in his autobiography:

For a group of scientists to declare so publicly that a colleague has made a technical error is serious enough. To link him with racist eugenics and Nazi policies was, in the overheated academic atmosphere of the 1970s, far worse. But the self-proclaimed position of the Sociobiology Study Group was ethical, and therefore implicitly beyond challenge. And the purpose of the letter was not so much to correct alleged technical errors as to destroy credibility.

Over the next year or so, opposition to sociobiological explanations of human behaviour slowly gained traction. A campaign of flyers was instigated by the Boston branch of the Committee Against Racism (CAR), teach-ins were held to oppose sociobiology, and for a time a protester on Harvard Square called for Wilson’s dismissal.

The language employed was predictably incendiary. CAR, for example, released a flyer alleging:

Sociobiology, by encouraging biological and genetic explanations for racism, war and genocide, exonerates and protects the groups and individuals who have carried out and benefited from these monstrous crimes.

In a later missive, the same group claimed that Wilson should be considered leader of a group of “scribblers” at Harvard who were working overtime to give a “respectable” cloak to racism. The flyer ended with a call to arms:

Militant action, not merely academic debate, is needed to crush Wilson’s fascist theories.

Wilson received little support from his colleagues. In his words, to be seen as a reactionary professor at Harvard made him as welcome there as an atheist in a monastery. He considered offers of professorships away from Boston, worried about the impact of the controversy on his family, but said he received little hate mail and never a death threat.

However, in February 1978, the attacks on Wilson did cross over a line into direct physical confrontation at a specially arranged symposium on sociobiology, during the annual meeting of the AAAS (American Association for the Advancement of Science) in Washington.

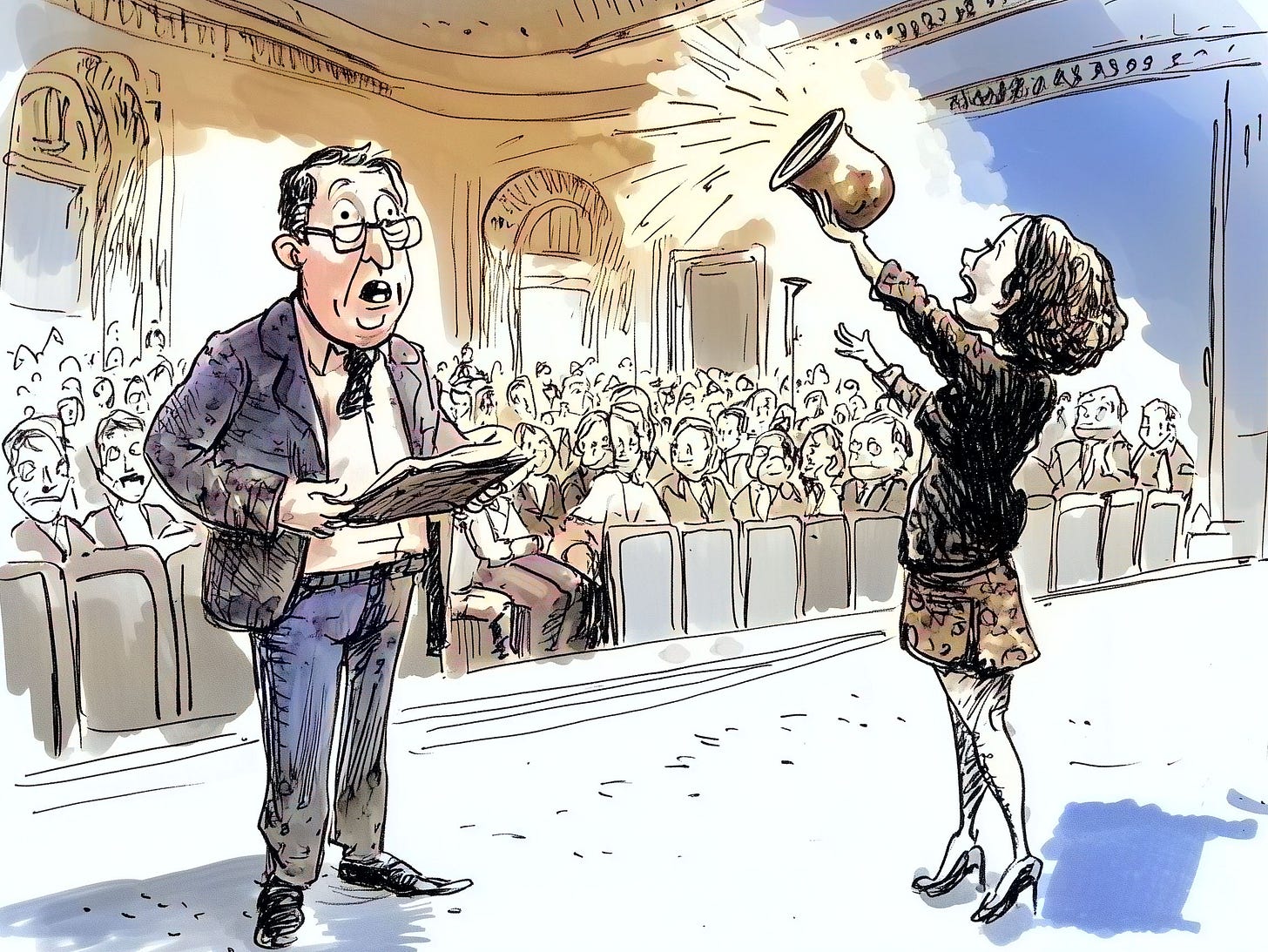

The atmosphere had been febrile even before the symposium began, with a demonstration planned by the Committee Against Racism, a group known for violence. On the day of the event, Wilson was not the first to speak, and several papers had already been given, including one by Stephen Jay Gould, before he took the stage. As he was being introduced to the symposium, a group of young men and women burst onto the stage carrying anti-sociobiology placards, including at least one painted with a swastika. Members of CAR took control of the session microphone, and began to harangue the crowd. At the same time, a young woman - with some hesitation, according to one account - grabbed a pitcher of water, and poured it over Wilson’s head, with the group chanting “Wilson, you’re all wet!”

Pathetic, but perhaps ultimately innocuous, you might think. Except the group also chanted, “Racist Wilson, you can’t hide, we charge you with genocide”, an obviously serious accusation, potentially disastrous for Wilson’s reputation and career if it came to be generally accepted. However, the optics of the protest were terrible for the anti-sociobiology side, and the major players in Science for the People, were quick to dissociate themselves from the CAR action, with Gould using Lenin’s words to condemn the protest as an “infantile disorder”.

He was right. The incident handed an easy victory to Wilson. Alice Henry, a commentator far from sympathetic to the sociobiology cause, had this to say about the protest after witnessing it firsthand:

The crowd booed. The chairman apologized. Wilson looked a little pleased and received a moderate standing ovation that he would never have gotten without the benefit of guerilla theatre. …A fellow from the Committee Against Racism spoke on how scientists resigned from the Eugenics society way back when but did not protest loudly enough. I agree that loudness is necessary, but think we need to shout about evidence. Slogans and physical assault had no visible effect on Wilson's thinking, on the audience's reception of Wilson's ideas, or on the way most people think about sex and race.

Wilson himself reported that he had felt calm, almost icy cold, as the protesters’ anger washed over him, concurring with Gould that it was the action of juveniles. He commented that he knew perfectly well that it was the grown-up intellectuals that he had to worry about.

There is an interesting side note to these events. The moderator of the 1978 meeting was anthropologist Margaret Mead. Two years earlier, at the annual meeting of the American Anthropological Association, a resolution to censure sociobiology had been defeated – by a narrow margin. “Book burning, we’re talking about book burning”, Mead had insisted, opposing the resolution.

The debate over sociobiology shifted ground in the 1980s with Wilson taking a step back to pursue an interest in issues to do with biodiversity. For the first half of that decade, the critics of sociobiology remained as vociferous as ever, targeting any scientist they suspected of the sin of “genetic determinism”. Richard Dawkins, in particular, was in the crosshairs, and he was more than happy to return fire. In a review of Not in Our Genes, a book criticising sociobiology by Steven Rose, Lewontin and Leon Kamin, Dawkins, in typically combative style, had this to say about Rose et al’s propagandising:

Rose et al. cannot substantiate their allegation about sociobiologists believing in inevitable genetic determination, because the allegation is a simple lie. The myth of the ‘inevitability’ of genetic effects has nothing whatever to do with sociobiology, and has everything to do with Rose et al's paranoic and demonological theology of science.

This did not go down well with the authors of Not in Our Genes, with Steven Rose reportedly threatening to sue Dawkins for libel (though ultimately nothing came of it). This brings up an interesting point about the conflict over sociobiology that is flagged up by sociologist Ullica Segerstråle in Defenders of the Truth, her comprehensive analysis of the affair.

Segerstråle points out that there is a double standard in play when it comes to how the respective parties were expected to behave. The critics of sociobiology

felt that they could require sociobiologists and others to be careful in their actions and choice of words, while they did not see the need to censor their own language when they accused the former of political intent. Sociobiologists were held to high standards, while the critics of sociobiology felt they could get by with easy dismissals of sociobiological theorizing… Antisociobiologists were allowed to see all sorts of links between sociobiology and unsavory politics, but the sociobiologists were not allowed to respond that sociobiology’s alleged political intent was a ‘lie’.

Segerstråle suggests that this indicated a move by the academic left to enforce a new norm in science, a norm that holds that scientists are responsible both for the content of their research and for any potential political misuse of their work.

Forty years on, we know that the critics of sociobiology were not successful in shutting down enquiry into the biological forces that shape social behaviour. In 2006, in an afterword to the 25th Anniversary edition of his autobiography, Naturalist, Edward Wilson summed up the then current state of play as follows:

The thrust of criticism in the 1970s and 1980s, which arose from the now discredited conception of the human brain as a blank slate, was that sociobiology entails a belief in biological determinism. This was a canard, and one mischievously intended. Sociobiology is not a doctrine or a particular conclusion but a discipline, an open field of inquiry, allowing in theory for the human brain to be a blank slate (disproved), or completely hardwired (never claimed), or the product of interaction between genetic predisposition and environment (well established and now almost universally accepted).

Edward O. Wilson died at the end of 2021 with his reputation intact. The scientific community mourned his passing, and tributes to his life and work flowed in from across the world. Among those paying their respects were Bill Clinton, Paul Simon and Leonardo DiCaprio. The attempted cancellation turned out to have been something of a damp squib.

Sources

Sociobiology, Edward O. Wilson

Naturalist, Edward O. Wilson

Defenders of Truth, Ullica Segerstråle

Not in Our Genes, Steven Rose, Richard Lewontin, Leon Kamin

“Against Sociobiology”, The New York Review, Elizabeth Allen, Barbara Beckwith, et al

“Sociobiology: the debate continues”, New Scientist, Richard Dawkins

“Questioning Authority”, Off Our Backs, Alice Henry

With thanks to Kerrie Grain.

It is very interesting when an event of this magnitude hinges on a logical error. I always expect reason to finish an argument, but people will sweep it aside and continue on.

I haven't checked in on Evolutionary Psychology in quite a while, but found it compelling. Compelling enough to defend, surely.