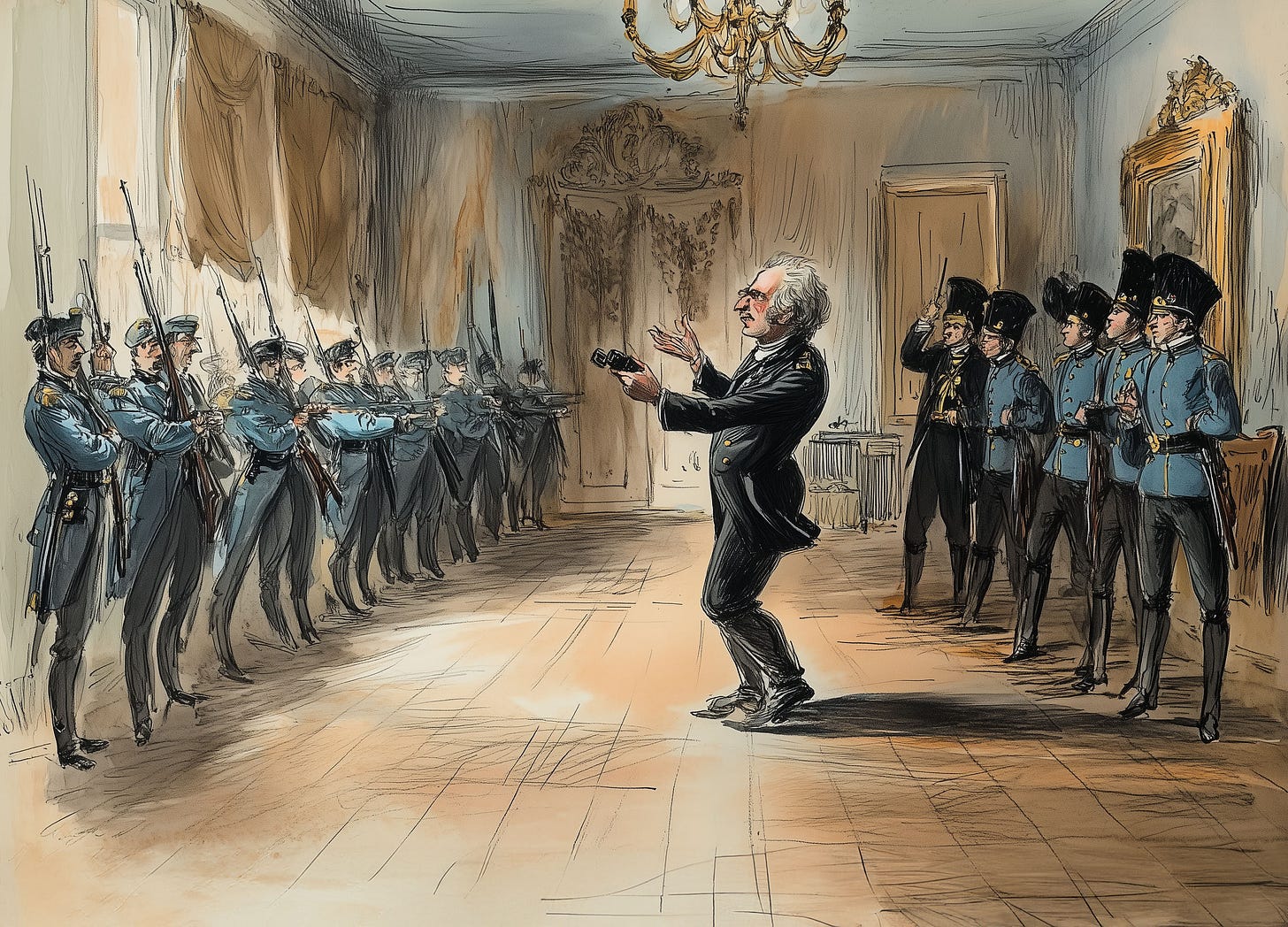

Schopenhauer and the Opera Glasses

The great philosopher comes to the aid of the Austrian army.

The year 1848 was decidedly nerve-wracking for the established rulers of Europe. Not only had Marx and Engels published their Communist Manifesto at the year's beginning, calling on the proletariat to rise up and throw off their chains, but bourgeois-democratic and progressive forces were out on the streets of European capitals, demanding the overthrow of the old quasi-feudal order. Before the year was out, France, Italy, Denmark, Germany, the Austrian Empire and the Netherlands had seen popular uprisings, the monarchies in France and Denmark had fallen, and serfdom had been abolished in Austria and Hungary.

Not everybody was sanguine about this upsurge in revolutionary consciousness. Holed up in his Frankfurt apartment, Arthur Schopenhauer, who had written so powerfully of the importance of compassion, was worried that the "sovereign canaille" - the rabble on the streets - would deprive him of his wealth. He dismissed the leaders of the German revolt as "students gone wrong" and suggested that the materialism of their philosophy - eat, drink, there is no pleasure after death - was a kind of bestialism. His biographers report that he began to economise, gave up his daily lunches at the Zum Schwan inn, and was prone to bouts of rage and fearfulness.

Matters came to a head in Frankfurt on September 18th, when the simmering tension of the previous months spilled over into violence, sparked by the new German parliament's endorsement of a peace treaty between Denmark and Prussia that favoured the status quo. The result was barricades on the street, the brutal murder of two conservative politicians, and a bizarre encounter between Schopenhauer and the Austrian army.

Schopenhauer's apartment on the Schöne Aussicht afforded the philosopher a good view of the day's tumultuous events, and he didn't much like what he was seeing. His biographer, David Cartwright, reports that he watched "a disorderly crowd of people armed with poles, pitchforks and rifles pour across the bridges from Sachsenhausen." Snipers from the Austrian army took up strategic positions, and fired into the crowd.

It was at this point that things took a rather surreal turn. Schopenhauer heard a commotion outside his locked apartment, followed by loud banging on his front door. Fearing that the sovereign canaille had finally tracked him down, he left it to his maid to go see what all the fuss was about. She reported back that it was not the rabble at the door, but rather the Austrian army. Schopenhauer was thrilled.

Immediately I opened the door to these worthy friends. 20 stout Bohemians in blue pants rushed in to shoot at the sovereign canaille from my window. Soon, however, they thought better of it and went to a neighboring house. From the first floor the officer reconnoitered the crowd behind the barricade. Immediately, I sent him my big, double opera glasses...

The idea, of course, was for the officer to use the glasses as a rifle-sight to make it easier for him to take pot shots at the rabble in the street below.

It is fair to say that Schopenhauer was not a great fan of revolutions; he was, as Bryan Magee puts it, "a counter-revolutionary, a reactionary in the strict sense of that word." It is no great surprise, then, that he called for Robert Blum, one of the leaders of the Frankfurt uprising, to be hanged; that he sang the praises of Prince Alfred Windisch-Graetz for successfully quelling the rebellion; and that a few years later he left a large sum in his will to the "fund for the relief of the Prussian soldiers who... had become disabled in their struggle for the maintenance of law and order in Germany, and of the next of kin of those who had fallen in this struggle".

Sources

David E. Cartwright, Schopenhauer: A Biography

Rüdiger Safranski, Schopenhauer and the Wild Years of Philosophy