The Fat Man and the Cave

Drown, or kill a fat man? Philippa Foot helps you choose.

Philippa Foot, continuing in the honourable philosophical tradition of imagining people trapped inside a cave, asks us to consider the following scenario.

A very fat man is leading a party of potholers out of a cave when he gets stuck in its mouth, trapping the others behind him. Clearly, the right thing to do is to sit down and wait until help arrives or the fat man grows thin, but unfortunately flood waters are rising within the cave. Luckily, the trapped party have with them a stick of dynamite, with which they can blast the fat man out of the cave. Either they use the dynamite, thereby killing the fat man, or they drown.

The obvious question here is whether it is morally permissible for the potholers to effect their escape by blasting the fat man into the stratosphere.

It is tempting to react to this scenario by claiming that it is too divorced from reality to allow one to come to a proper judgement. If you were actually in this situation, it is unlikely you’d know for certain that the dynamite would be effective, or that everybody would die if you did not blast the fat man out of the cave. The real world is messy and unpredictable, which means that moral judgements are often made on the basis of imperfect information. In contrast, our scenario is set up to give us a god’s eye view of everything, and, to this extent, or so it might be argued, it is flawed as a way of examining moral decision-making.

However, this objection misses the mark. The scenario depicted here aims to shed light on the processes governing our moral reasoning precisely by abstracting from the messiness of the real world. The idea isn’t to reveal what we’d actually do, but rather to show what principles we draw upon when thinking about what we ought to do. In this case, it means reflecting upon how we weigh up the value of one life against the value of many lives, and, more generally, the value of fewer lives against the value of a greater number of lives.

The Trolley Problem

The trolley problem provides a means to examine this issue without getting bogged down in all the complexity of the real world. The trolley problem was originally devised by Philippa Foot, first appearing in her 1967 essay, “The Problem of Abortion and the Doctrine of Double Effect.”

Foot couched the problem in terms of a decision faced by the driver of a runaway tram, who can only steer from one narrow track onto another. Five men are working on one track and one man on the other, and anybody on the track the driver chooses is bound to be killed. Foot took it as a given that the driver should turn his tram, arguing that this is obligated because of a “negative duty” to avoid doing harm to the five on the track:

The steering driver faces a conflict of negative duties, since it is his duty to avoid injuring the five men and also his duty to avoid injuring one. In the circumstance he is not able to avoid both, and it seems clear that he should do the least injury he can.

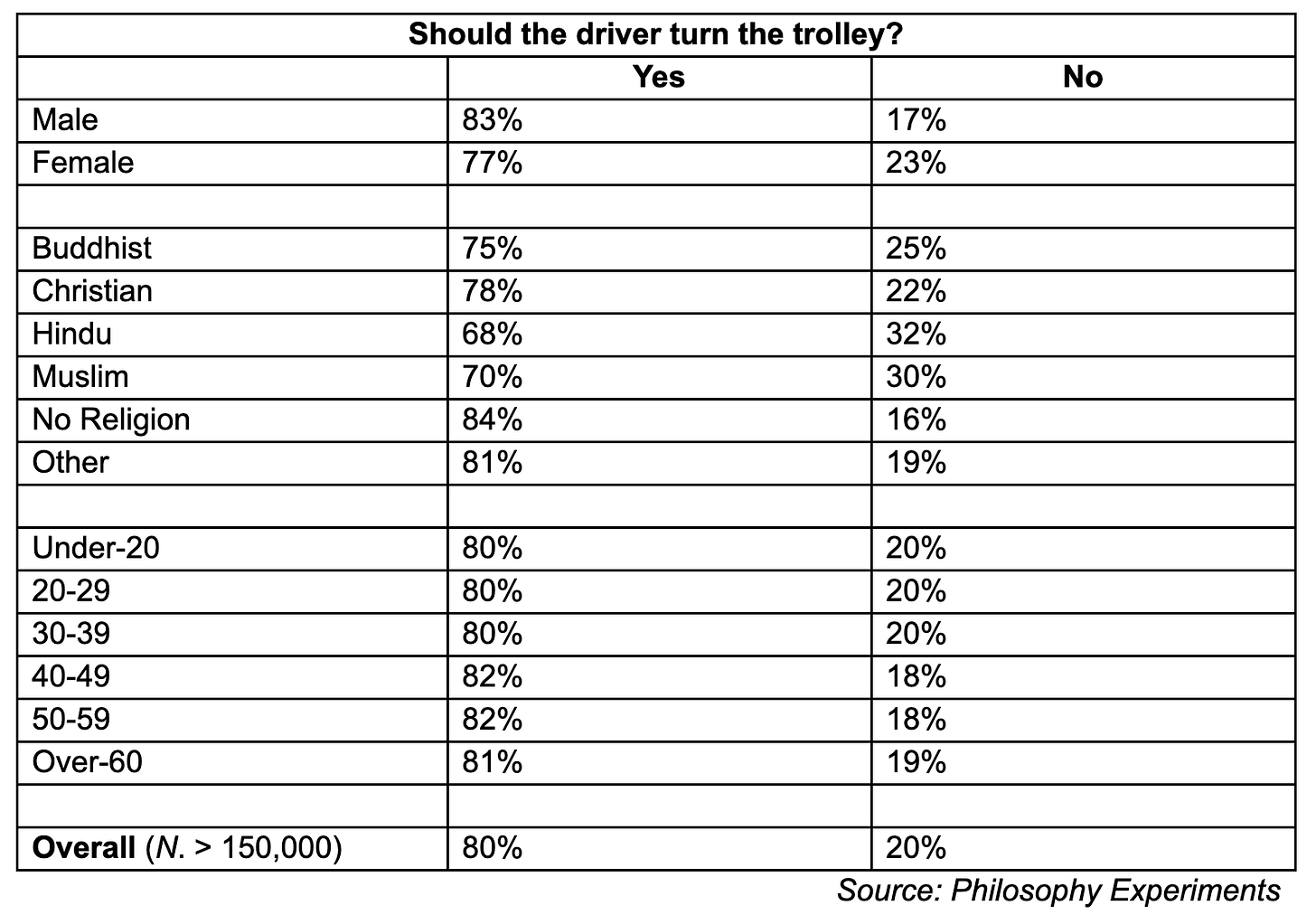

Foot’s belief that the driver should steer for the less occupied track is shared by the great majority of people who are asked about the trolley problem. According to data collected at the Philosophy Experiments web site, approximately 80% of us think the driver should turn the trolley, a figure that varies only marginally across sex, religion and age.

It might be tempting to conclude from this level of consensus that there isn’t going to be much mileage in the trolley problem. It seems straightforwardly the case that most people believe saving more lives justifies sacrificing fewer lives. However, such a conclusion would be premature, not least because it is easy enough to come up with scenarios where our moral intuitions tend to go in the opposite direction. For example, Foot asks us to imagine a situation in which it would be possible to satisfy a rioting mob’s desire for bloody revenge by killing an innocent person, and then passing the innocent person off as the perpetrator of the crime that sparked the mob’s ire. She remarks that we would find ourselves “horrified” by such a course of action, even if it were to result in lives being saved. So why this difference? Why do we think turning the trolley is morally justified, but killing the innocent person isn’t?

Positive and Negative Duties

Foot’s answer to this question rests upon a distinction between the negative duty to refrain from causing injury and the positive duty to provide aid. Examples of the former would include the prohibitions against murder and violent assault, but also the requirement to hit the brakes if somebody steps in front of your car. Examples of the latter include the duty to provide warmth to somebody suffering from hypothermia; and, more generally, the duty to alleviate human suffering.

Foot argues that our different reaction to the trolley problem and the rioting mob scenario is explained by the fact that the negative duty to refrain from causing injury is stricter than the positive duty to provide aid. Thus, in the trolley setting, the driver is faced with a situation where he cannot avoid doing harm, so it is his (negative) duty to minimise the amount of harm he causes, which means he must turn his trolley.

The rioting mob scenario, however, is different. Here the choice is between, on the one hand, causing injury to an innocent person – by framing and killing them – in order to provide aid to bystanders who will be harmed if the mob’s bloodlust is allowed to play itself out, and, on the other hand, not coming to the aid of these same bystanders, with the consequence that some number of them will die. It might well be that the only way to help those caught up in the mob’s fury is to frame an innocent person, but this would not be justified, because it would violate the negative duty to avoid doing injury, which here holds sway over the positive duty to provide aid. It follows that there is no inconsistency in thinking that the innocent man should not be framed but the driver should turn his trolley, for the simple reason that we don’t have the same duty to help people as we do to refrain from injuring them.

This argument undoubtedly has some force. Consider, for instance, another example to which Foot draws attention.

We are about to give a patient who needs it to save his life a massive dose of a certain drug in short supply. There arrive, however, five other patients each of whom could be saved by one-fifth of that dose. We say with regret that we cannot spare our whole supply of the drug for a single patient… We feel bound to let one man die rather than many if that is our only choice.

However, although we would allow the one man to die, given this scenario, we would not countenance killing the same man in order to make a serum from his body, even if this could be used to save the lives of the same five dangerously ill patients. The difference in the latter case is that we would have to cause injury in order to provide aid, rather than simply choosing between aiding one person and aiding five people.

So, to reiterate, Foot’s claim is that the moral duty to refrain from causing injury is stricter than the moral duty to provide aid, which means you can’t assume that actions are morally identical just because they result in the same amount of good and evil. As we have seen, it doesn’t follow that because a trolley driver would be justified in steering towards a less occupied track to save five people, that a judge would be justified in framing and killing an innocent person to prevent the same number of people dying at the hands of a rioting mob.

Let’s return now to our fat man stuck in the mouth of a cave to see whether Foot’s distinction between negative and positive duties sheds some light on how we should proceed in that situation.

Stuck Fast in a Cave

The first thing to note is that there are two versions of the fat man in a cave story, one of which is relatively easy to sort out, the other, a lot more difficult. In the first version, the fat man is stuck with his head pointing inwards towards the rising waters, which means he is certain to drown along with everybody else. Here things seem more or less straightforward. The fat man is going to die whatever happens, which means, given that we have a positive duty to aid people in danger of imminent death, it is reasonable to save those people who can be saved, even if this means bringing about the death of the fat man. Of course, some people will insist that deliberately killing an innocent person is never justified, but, as Foot points out, the great objection to this edict is precisely that it applies even in a case such as this one - imagine, for example, that there were a million people stuck behind the fat man.

The second version of the story, however, is much more difficult to sort out. This has it that the fat man is stuck with his head pointing out of the cave, which means that while everybody stuck behind him is going to die, he isn’t. In this situation, negative duties being stricter than positive duties would seem to count against blasting the fat man out of the cave. Put simply, Foot’s position entails that the fat man has rights against the potholers trapped behind him, which may or may not be decisive, to the effect that they should not harm him in order to make their escape.

There is some support for the idea that it would be wrong to kill the fat man in this second version of the story by analogy to a scenario that frequently crops us in these discussions, which has is that it is possible to save the lives of five desperately ill patients by harvesting the organs of a young man in perfect health. In both the second version of our fat man scenario and the organ transplant situation, we can save five people, but only by killing a single other person, whose life would not otherwise be in danger. In the organ transplant case, most people recoil from the idea that it could be morally permissible to harvest the organs of a healthy bystander, so it would seem to follow that we ought to be similarly reluctant to sacrifice the fat man.

However, it is at this point that the complexity of the real world comes crashing in. In particular, there are a number of subtleties in the cave situation that are likely to affect how we view its moral dimensions.

The cave situation differs from the organ transplant case in that the fat man is causally implicated in the danger that is unfolding - if he were not stuck in the mouth of the cave, then the potholers would be able to escape. The moral significance of this point is a complicated matter. Perhaps, for example, it is the case that the fat man ought to have anticipated that he was likely to get into difficulty, and that to this extent he is the author of his own misfortune; or that the trapped potholers have what are effectively self-defence rights against the fat man, which trump his right not to be harmed; or that the fat man has a moral obligation to sacrifice his own life, given that he is part of the reason the potholers are in trouble. None of these points is necessarily decisive, but all are indicative of the complexity of the situation.

Also, it is at least arguable that numbers make a difference here. It might be the case that while it would not be morally permissible to sacrifice the fat man to save five lives, it would be permissible to sacrifice him to save one hundred lives or a thousand lives. Here thoughts about consequences are to the fore, which brings into sharp focus the possibility that there is some amount of harm, the avoidance of which would justify violating the fat man’s right not to be injured.

It is possible, of course, that there is no definitive answer to the question of whether it would be permissible to blast the fat man out of the cave. Foot readily admits there are many situations where the moral calculus is just very difficult. However, this does not undermine her main point, which is not that it could never be morally justified to violate the negative duty not to cause injury, but rather that this duty imposes stricter obligations than the positive duty to bring aid, and that this will often be an important consideration in determining what is right and wrong.

Trolley Problem Dissolved?

Although Foot’s distinction between negative and positive duties is unlikely to generate a clear statement of how we should proceed in the second version of the fat man story, it does seem to dissolve the puzzle of the trolley problem. As we have seen, there is no inconsistency in thinking that one life for five lives is justified in the case of the out of control trolley, where it is inevitable that the driver will kill either one person or five people, but not necessarily justified in cases where what we’re talking about is killing one person to save the lives of five people. To put this another way, there is a difference between killing and letting die, rooted in the relative importance of the obligations imposed by negative and positive duties, such that it is morally justified to kill one person rather than five people, if there is no choice but to kill either one or five, but not necessarily morally permissible to kill one person, where the choice is between killing one person or letting five die.

It is worth putting that a little more simply to make sure the point is clear. Killing a person violates the negative duty not to injure; letting people die violates the positive duty to bring aid; but, crucially, the former has priority over the latter, so it isn’t possible to argue from the fact it is better to kill one person rather than five people to the conclusion that it is better to kill one person rather than letting five people die.

If Foot is right, and the trolley problem is dissolved simply by paying attention to the relative importance of negative and positive duties, then it is curious that the problem has attracted so much philosophical attention over the last sixty years. In fact, Foot’s solution does not work in the way she hoped. To understand why, you need to take a look at the work of the American moral philosopher, Judith Jarvis Thomson, whose treatment of the issue catapulted it to the philosophical fame it enjoys today.